14. Reflections.

"Have patience with everything unresolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves as if they were locked rooms or books written in a very foreign language. Don't search for the answers, which could not be given to you now, because you would not be able to live them. And the point is to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps then, someday far in the future, you will gradually, without even noticing it, live your way into the answer."

Rainer Maria Rilke (Letters to a Young Poet)

The Meaning of Existence

Everything except language

knows the meaning of existence.

Trees, planets, rivers, time

know nothing else. They express it

moment by moment as the universe.

Les Murray

Carmen: How vividly I recall learning to walk again, wobbling along on a frame, until one day I threw it aside — being able to walk unaided signposted my return to the living world. I remember the joy I felt at the rediscovery of ordinary things — just to sit comfortably in a chair was a delight, to be able to make my own cup of tea, to shower myself, just to dress and undress without help was wonderful. I turned my mind and energy to making our house more homely. I went shopping with Michael and my delight was childlike. We bought furniture and I picked out cushions and curtains and had marvellous fun choosing patterns and colours. I cooked a meal for invited guests. Michael and I went to a dance. I turned again and again to the idea of writing a doctoral thesis.

I became stronger. I began to join in community activities. I joined a local choir. I started belly dancing and stretching exercise classes. Michael was less sociable. He promised he’d accompany me to play croquet (I’m still waiting). I became more and more focused on my intended doctorate. I was astonished when I realised I was well enough to start work on it. Returning to Southern Cross University, I had a long talk with my supervisor Professor Beverly Taylor. My illness gave me the title and the theme of my thesis. Professor Taylor was enthusiastic. It was to be about dying. But not about dying at all. It was about ‘being alive’ to the process of dying. And being healed.

My topic is my life story which is a bundle of bits and pieces, shreds of memories that parachute all over the place and are quite unreliable, and it speaks of people I have loved who move in and out of my life, and it tells of experiences. Life is simply an experience, a window of perception.

******

Winter 2006: I am stronger but must husband my energy. I think ahead to the time when I have my doctorate and I’m robust enough to return to work. I try not to peer too far into the future. Michael says people yearn for their life to be foreseeable. But it can never be that. I am wary of probabilities and predictions — during my illness these were constantly thrown at me. It happened again when I had to fill out a form with my doctor so that I could get medical benefits.

“I must attach a medical prognosis to the description of your disease,” he said. His pen was poised over the form. “Terminal!” He wrote it down. He didn’t look at me. I was shocked. It was such a careless thing to say. “You speak like God telling the future,” I responded to him angrily. He shrugged his shoulders. His discipline was logico-deductive. In his eyes I was a clock running down. He could approximate the time when I’d stop. I told him I was not Schrödinger's cat. “I am not a thought experiment,” I cried.

******

Spring 2007: Scientists from around the world suggest the weather is changing dramatically. Here in Kyogle we are in hilly forested country that normally receives heavy rainfall, but for some months there has been a drought. Forecasters predict the dry spell will continue. Locals are resigning themselves to a time of hardship. Our council is enforcing water saving restrictions.

Their forecasts are wrong. It is a good idea to be wary of probabilities and predictions

Suddenly we are having a huge downpour (nature being as unpredictable as ever). It has been raining steadily for three days, sometimes accompanied by thunderstorms and hail and strong winds. The weather is capricious, scientists are right about that, which everyone knows anyway. Thunder rattles the windows and rain roars on the iron roof. Michael and I sit on the veranda at night and watch lightening, tongues of fire, heavy clouds bursting out in flashes of white and silver.

I found two miserable and bedraggled maggies on the veranda and they didn’t move when I walked past. This evening, in front of the house, I saw a pink and grey Galah hanging from the phone line by one claw with its wings drooping, swinging and screeching mawkishly.

Rain is a life giver. Things must really have been getting desperate for the frogs around here. Last week, before the rain, I found one in the middle of the night in the cistern of our toilet. It was a beautiful green tree frog, larger in size than usual. Michael has decided to make a pond. We hope to get tadpoles.

Summer: We are feasting on mulberries from the garden, and we notice that the tropical apple tree, the mango and citrus trees are full of blossoms — promises of more delicious feasts to come. It is a good location for growing things, the soil is volcanic and plants love it. I love it here.

******

Immediately surrounding us are undulating hills and valleys, a rolling fertile green countryside that grows avocados and bananas and custard apples. There is a white Charolais bull in the field below our house. A short way down the road there is a dairy from which our milk comes. Michael’s Celtic blood allows him to have creamy milk and other animal fats (opposite to me). I like the taste but can’t digest the cream.

Kyogle is built on the slopes of Fairymount — it’s a hill, not a mountain. I love the names around here. ‘Fairymount’. ‘The Risk’. ‘Summerland Way’. ‘Lions Road’. ‘Green Pigeon’. Where are the ancient Aboriginal names for these places?

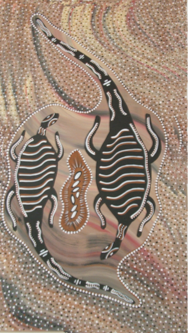

Bundjulahm talks of her sadness’ at the loss of her culture, and yet she knows her people must embrace the future. I have a beautiful poem written by Oodgeroo Noonuccal, of the lands of Minjerriba. It describes the feeling of resignation and the glimmering of hope that she, a beautiful and wise Aboriginal crone feels for her people:

Understand, Old One

Understand, old one,

I mean no desecration

Staring here with the learned ones

At your opened grave.

Now after hundreds of years gone

The men of science coming with spade and knowledge

Peer and probe, handle the yellow bones,

To them specimens, to me

More. Deeply moved am I.

Understand, old one,

I mean no lack of reverence.

It is with love

I think of you so long ago laid here

With tears and wailing.

Strongly I feel your presence very near

Haunting the old spot, watching

As we disturb your bones. Poor ghost,

I know, I know you will understand.

What if you came back now

To our new world, the city roaring

There on the old peaceful camping place

Of your red fires along the quiet water,

How would you wonder

At towering stone gunyas high in air

Immense, incredible;

Planes in the sky over, swarms of cars

Like things frantic in flight.

What if you came at night upon these miles

Of clustered neon lights of all colours

Like a Christian newly come to his Heaven or Hell

And your own people gone?

Old one of so long ago,

So many generations lie between us

But cannot estrange. Your duty to your race

Was with the simple past, mine

Lies in the present and the coming days.

Oodgeroo of the Noonuccal of the land, Minjerriba.

Oodgeroo’s poem leads me to thinking of a friend in Perth, Wild John. His toilet is in the garden, and his bath, and he cooks outside, and sleeps on the grass in a bushman’s swag. He uses his modern brick and tile house to store machinery and bicycles. He’s as fierce as a Viking, blond and bearded. I think of him because he is a true mystic. The way he talks reminds me of Les Murray: ‘Everything except language knows the meaning of existence’. Wild John’s not good with language, but he has extraordinary gut-wisdom. He loves everything wild and untamed and talks of trees and plants and animals as if they are companion friends. “Every living thing has energy,” he says, “and I can feel the surge of it. I know when I’m living truthfully when I feel ‘good’ energy surge in my own gut.”

I too know this is true because when I am being natural I feel I am holy — I had to nearly die to drop all my sophistications. The true meaning of the word sophisticated is spoiled. When I think of Wild John I’m reminded of Saint Francis of Assisi, to whom everything was brother or sister, father or mother — I’m not a mystic, and yet I know in my bones this is right.

‘The men of science coming with spade and knowledge

Peer and probe, handle the yellow bones,

To them specimens, to me

More. Deeply moved am I’.

******

Reflections: I don’t know how long my life will be. I’m delightfully alive now. Now! My shamanistic friends, contemporary medical, and alternative complementary, have helped extend the length and breadth of my life. But not its depths.

My life is energy, purely. I sometimes have pain in my body, mostly in my bones, and I feel it move. Body pain is energy moving from place to place. Deeply moved am I.

I am painting and writing and striving to complete my thesis. It is a productive and happy time. But time is short.

I have received a beautiful card and with it in the envelope came a feather (from an owl or guinea fowl?). A coincidence because I painted a feather landscape for my PhD thesis. The feather is my totem.

******

"For the time being the highest peak, for the time being the deepest ocean; for the time being a crazy mind, for the time being a Buddha body; for the time being a Zen Master, for the time being an ordinary person; for the time being earth and sky... Since there is nothing but this moment, 'for the time being' is all the time there is."

Zen Master Dogen

Michael: Dismay! Carmen asked me what I’d do with myself ‘when’ she died. It came out of the blue; we’ve been so quiet and peaceful here and very happy. This morning she was in her studio and I could hear her singing. I made lunch and we had it on the veranda, and she remarked, almost in passing, in a sort of ‘oh by the way’ tone of voice: “I feel really hurried to finish my doctorate because I don’t have much time left to me … what will you do with your life when I die?”

Carmen: My memories seemed disconnected from time. I was sitting at my easel painting The Silent Scream. I wanted to capture the feeling, as it was, and place it on the canvass, to convey my desperation that people could not hear my inner scream of anguish. In my mind I went back to the hospital room, to those blue walls, to the smell of flowers and sharp antiseptic, to the scent my nurse was wearing, to the sound of a rattling trolley, and in the distance a phone ringing. I was there! I returned to the moment. I screamed out loud and Michael rushed in. He found me standing before my easel with my hands to my head and with an expression of agony on my face. My memory of the moment returned and I (re)lived it fully; a flash of lightening scorched me. Ouch!

It is true, from my experience, that really looking closely at dying is like trying to look at the sun. I couldn’t move or speak. I tried to look at what was happening to me, to look inwards, but I couldn’t see. It was dazzling, like the sun. There was no light in my eyes, but still it dazzled me. The best thing, the pain went away. Then it was almost pleasant.

Later in the night I remember envisioning the most calming landscape, of a sunset over a forest. That type of vision is conducive to creating beauty and calmness — which is the complete opposite of the lived reality of metastatic cancer. I suppose you could call that a kind of distraction, or self-supporting mechanism, a way of making a painful and horrific reality bearable.

Memory: Michael was there. My lovely Michael. I wanted to fill him with a sense of hope. They told me before, I can’t remember when, that the cancer was going to kill me. I was feeling quite healthy at the time, really good in myself. They said a year. I believe giving a person a time limit, a death sentence, can be so aggressive and such an imposition. The fact is some people do survive against the odds, and that fact inspires hope. I wanted Michael to have hope, maybe that I’d get better, or if I died then, well, it would be alright. Of course, I’m aware, there is no need for giving false hope. A hospice worker once told me that you neither give (false) hope nor do you take it away. She believed that people are generally naturally hopeful, and that has been my experience. To be hopeful and honest is most important.

Memory: I said to the doctor that I wanted to live. Which didn’t mean I was frightened of dying, frightened of what was happening to me. I just wanted to be alive — which is such a mystery: who am I who is experiencing this who wants to be alive? Such a mystery it is, to be here now. To feel the sun warming my face. Death is cold. Of course I wanted to live. I strived for life. I was not yet ready to give up the wonder of it, particularly when I saw the suffering my circumstances created in others. Michael was weeping. He was crying like a child. I was so sorry.

There were some things that took place when I became aware of impending death: one thing was that when I felt well I also felt optimistic, and the opposite was also true when I saw death’s face. It’s like there is a part of you that is in fact functioning well and that part is not aware of dying. It is in fact not dying. There are other parts that are not functioning well, and those parts are aware that they are diseased and may never recover. It is as if one or the other part is at the foreground at different times. And perhaps when there are enough parts that know they are dying, then acceptance can take place.

There is another thing to consider. I have a sense that the essential experience of the self, the ‘I’ experience, seems to be consistent regardless of age or changed circumstances. So consistent in fact that it feels like it will still be there afterwards — I was thinking then, of the word ‘oblivion’, but oblivion is merely a concept. Living and dying are not concepts. I have seen others who cannot believe they are going to die even though their physical appearance and medical diagnosis makes it obvious to everyone else. Maybe we are at times aware of that part of us that does not in fact die — our soul-self perhaps, that does in fact survive our physical body’s death.

I have come to the understanding that for me to feel wholly ‘ready’ for death I have to actively deal with the unfinished business in my life. I am making every effort with my family and friends to resolve disputes as far as possible. I, like every other person, do not know exactly when I will die. All I know is that I am alive. Even when I am dying, I am living. When I was lying in that hospital bed and I knew I was dying, I also knew I was alive, living, living, living … and so on.

Memory: One thing I was keenly aware of when I was very ill was Michael’s well-being. I really wanted him to have a life, and to keep himself well. There was no point in both of us passing away from life. I wanted him to get help, to take time out, to be with friends and to do enjoyable and recreational things. My Caring Circle people helped there. His welfare was important to me. I did not see that as being selfish at all.

When I was especially needy, I must say I did not want to be alone, but it did not have to be in Michael’s company all the time. Frankly, I don’t know how I would have survived without his gentle loving (and sometimes challenging) companionship. From my point of view his was a formidable task, a role that is definitely not for the faint hearted. He deserves to have a good life after I’ve gone.

The Thesis: What I want to communicate is much more creative and personally meaningful than what I did with my Masters degree (with Maria — who has changed her name to Mouna). The difference is that it is basically an autobiographical account and I am able to use my own artwork.

I will be giving a presentation of my thesis proposal to my uni’ mates. Fortunately the presentation will be informal, it will be more or less a round circle talk. It is heartening to me that there is a strong interest in this project, not only from family and friends but also from the university establishment.

Since starting this thesis I have come to realise that not many first hand accounts are available on the subject (not of dying — but living the experience of it). I record my own experience of dying with the hope it will inform others — I will record the coming experience of it until the moment my strength fails.

******